Teaching history is the art of storytelling. But storytelling has its dangers, as Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, author of my January adult book club book Americanah, warns in her TED talk "The Danger of a Single Story." She warns that only telling one story of a people leads to stereotyping and false assumptions, such as disregarding her Nigerian middle class upbringing as not "authentic", according to one of her American college professors, because it wasn't the starving/sick/poor/hard-scrabble story we Americans hear about Africans from our media. She asserts that only by telling multiple stories will we get the true meaning.

This idea of multiple stories, multiple sources, is a topic explored by Mary Janzen in her 6 Jan 2015 SmartBlog post "Using digital resources to enhance social studies, history instruction." She argues that the textbook version is too narrow, that it's the "single story", and that adding digital resources including many primary source documents, helps students to see history from multiple perspectives, without stereotyping or narrowing to only one story.

As we jump back into Early American History next week, my co-teacher and I are pushing pause before moving forward in the chronology. We finished our Colonial America unit right before the winter break, so we are going to linger for a couple weeks in some of the big ideas that formulate the Promise of America, our year-long theme. Many of the "promises" were formed during the colonial era: freedom of religion, self-governance, the free enterprise system, and equality (within contextual boundaries, of course).

One of the defining movements during the early 18th century was The Great Awakening, a time when itinerant Christian preachers spread ideas of breaking away from authoritarian religious practices, like the Puritans, and embracing the right to practice religion in a way that allows the common person to have a direct relation with God. A central tenant was that everyone is "equal" in the eyes of God, a very radical viewpoint for the times. Here is what the textbook closes its three paragraphs with: "By encouraging ideas of liberty, equality, and self-reliance, the Great Awakening helped pave the way for the American Revolution." (TCI, 2011).

So that's the single story: Preachers preached, people converted to their ideas, and the American Revolution was born. Hold on... we all know it's not that simple.

We are going to use the resource What Did the Great Awakening Awaken? (Social Studies School Services, 2007), a collection of primary source documents, both visual and written, that presents two sides of the story: the religious revivalists and the authoritarian establishment. It is set up to be used as a DBQ (Document-Based Question), with guided reading questions to scaffold understanding the documents before answering the question: "'The Great Awakening taught colonial Americans to challenge religious authority forcefully. This helped prepare them for the political revolution to come.' Assess the validity of this statement." However, instead of asking students to write a DBQ essay, we're going to hold a debate. This will build on our previous work with finding evidence, stating a rule, and drawing a conclusion (see previous post on this). Students will need to draw evidence from the primary sources to use in their debate argument, and justify their thinking with the rules and conclusions.

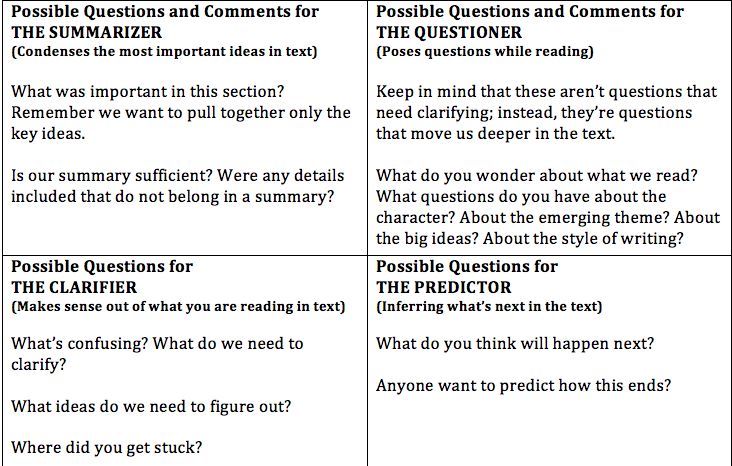

But first, students need to understand the sources. Eighteenth century writing style is very different from 21st century (especially digital and social media) writing style. Sentences are long; grammatical constructs are complicated; they use big words! Our eighth graders will struggle to understand the writing. This is why we are going to use Reading Workshop (mini-lessons on how to read informational text) and Reciprocal Teaching, a strategy we learned from visiting consultant Stevi Quate, to help them learn to read difficult texts. Groups of four students assume roles, and they tackle small chunks of the text together. Roles are rotated with each document, so students get practice with each type of thinking. Here is a "cheat sheet" we'll give students to help them get started:

There are four primary source documents in What Did the Great Awakening Awaken? That gives each student a chance to try out each role. By practicing this kind of thinking in a very structured, supported way, students will begin to internalize the strategies, and move closer to being able to read difficult texts independently. We'll see how well they do, and reassess how much scaffolding they need for our next Debating the Documents packet: Patriots and Loyalists. We may need to stay here for a while, or possible back off to pairs (each student gets two roles). By the time of the assessment, they should be able to tackle a text independently. But that's way down the road.

No comments:

Post a Comment